Valentine’s Day is around the corner, and at Deenista it got us thinking.

Not only about love expressed through rose bouquets or cards, but also about a deeper kind of love; the kind carried through literature, history, and lived tradition.

We are drawn to the love stories of Middle Eastern, Asian, and Persian heritage; the ones that rarely find space in mainstream narratives. Stories where love is not something you prove, but something you live with, shaped over time through language, art, and memory.

In these traditions, love is not always romantic in the modern sense.

It is devotional.

It is patient.

It is often unconditionally given, and that is not seen as a flaw.

In this post, we explore Gol o Morgh, the Persian art of the bird and the rose, alongside the many ways love has been named and understood; from eshgh (عشق) and hubb (حُبّ) to poetry, symbolism, and spiritual longing in Persian and Islamic culture.

The many words for love across Persian, Arabic, Urdu and Pashto

In our languages, love has many names.

Eshgh (عشق): consuming, transformative love.

A love that overwhelms, reshapes, and asks for surrender.

Hob (حُبّ): gentle, grounded affection.

Steady and enduring. A love rooted in care rather than intensity.

In Urdu, love often appears as mohabbat (محبت): warm, expressive, and emotionally generous.

It is the language of poetry and everyday speech, love that is spoken and shared.

In Pashto, love is mina (مینه): intimate, tender, and deeply human.

A word that feels lived-in rather than idealised.

Different words, different textures.

Yet across these languages, love is rarely transactional. It is something that shapes the one who loves.

Love beyond romance in Persian and Islamic art

This understanding of love; patient, asymmetrical, inward, has always found its way into art.

One of the most beautiful visual expressions of it lives in a classical Persian painting tradition known as Gol o Morgh.

In this post, we take a closer look at what Gol o Morgh truly means and how Deenista has interpreted it through art.

What Gol o Morgh actually means

Literally, Gol o Morgh means flower and bird.

Symbolically, it means the beloved and the lover.

Most often, the bird is the nightingale (bolbol) and the flower is the rose (gol); a pairing that runs through Persian poetry, Sufi thought, and visual art.

Gol o Morgh is not a decorative motif.

It is a philosophy of love.

The symbolism of the flower in Gol o Morgh

🌹 The flower (Gol)

The flower represents beauty, the beloved, perfection.

It is often still, composed, slightly distant.

It can symbolise:

- a human beloved

- divine beauty: God, truth, the eternal

- the unattainable ideal

The flower does not chase.

It does not explain itself.

It simply exists.

We returned to this idea in our own Gol o Morgh artwork.

The symbolism of the bird in Gol o Morgh

🐦 The bird (Morgh / Bolbol)

The bird represents the lover.

Restless, expressive, emotional.

Often shown leaning toward, circling, or singing to the flower.

It symbolises:

- devotion

- yearning

- the soul in search of meaning

The bird suffers, but willingly.

Love (عشق) in Persian culture

Together, Gol o Morgh becomes a portrait of unconditional love.

One is the beloved.

One is the lover.

One remains still.

One cannot help but sing.

This is not imbalance in the modern sense.

It is the language of عشق, a love that gives without measure, like Majnoon loving Leili, like the butterfly drawn to the flame.

In Persian culture, love is not something that must be returned to be real.

It transforms the one who loves, and that, in itself, is enough.

The spiritual meaning of Gol o Morgh in Sufi thought

In Sufi interpretation:

- the bird is the human soul

- the flower is divine beauty, God

Love is not possession.

It is proximity without ownership.

That is why Gol o Morgh never feels dramatic or theatrical.

It is intimate. Almost private.

Gol o Morgh in Persian poetry: Hafez and the nightingale

Few poets captured this symbolism as precisely as Hafez.

Hafez: Ghazal 277 (original Persian)

فکرِ بلبل همه آن است که گُل شد یارش

گُل در اندیشه که چون عشوه کند در کارش

Meaning:

The nightingale thinks only of this:

that the rose might become its beloved.

The rose, meanwhile, is occupied

with how to display its own beauty.

And later in the same ghazal:

بلبل از فیضِ گل آموخت سخن، ور نه نبود

این همه قول و غزل تعبیه در منقارش

Meaning:

The nightingale learned its song

from the grace of the rose,

otherwise, how could so much poetry

have been placed within its beak?

Hafez returns to this image to show love as unreciprocated devotion:

the lover consumed by longing,

the beloved complete in its own being.

This is Gol o Morgh at its purest.

If Hafez’s poetry speaks to you and you’d like to explore how his verses live on in Persian tradition, you can read more about his role in Yalda night and the ritual of fal-e Hafez in our contemporary Yalda Sofreh post.

“Gol o bolbol”: when poetry became everyday language

In modern Persian, the phrase «گل و بلبل» has taken on a different life.

When someone says:

فلانی گل و بلبل میگه

they usually mean that a person is speaking sweetly, using pleasant, flowery words. Compliments, charm, polite talk. Sometimes sincere, sometimes a little light, even a touch la-la-land.

It is striking how the language of art and poetry has found its way into everyday speech.

What once symbolised deep devotion and longing; the lover singing without expectation, has, in daily language, become shorthand for pretty talk.

Perhaps that, too, says something about how love travels through time from poetry, to painting, to language; changing shape, but never quite disappearing.

Why Gol o Morgh still speaks to us today

Gol o Morgh quietly speaks of:

- longing without entitlement

- love that survives distance

- beauty that does not need to respond to be real

- devotion as dignity, not weakness

Which is very Deenista.

The visual language of Gol o Morgh paintings

Traditionally, Gol o Morgh artworks are defined by:

- soft, restrained colour palettes

- natural balance rather than symmetry

- gentle curves, no sharp aggression

They appeared on:

- manuscripts

- lacquer boxes

- album pages

- and later, as standalone artworks

Even when decorative, the emotion is always inward.

Gol o Morgh and Valentine’s Day: another way of understanding love

As Valentine’s Day approaches, many cultures reflect on love in their own ways.

Gol o Morgh offers a language of love that sits alongside modern Valentine traditions, rather than replacing them.

Perhaps it is less about grand romantic gestures and heart-shaped chocolates, and more about quiet devotion. That inner love.

In its spiritual reading, this love can be directed not only toward another person, but toward divine beauty itself; a longing for God, truth, or the eternal.

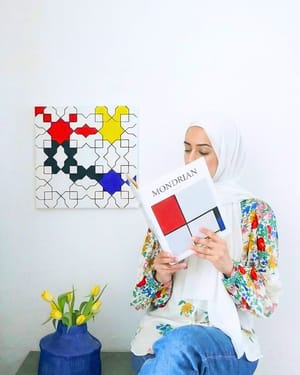

Our interpretation of Gol o Morgh at Deenista

At Deenista, we approached Gol o Morgh with both reverence and curiosity.

We created two artworks for homes drawn to a more devotional understanding of love. Artworks that honour tradition while allowing space for contemporary interpretation.

Gol o Morgh (Bird and Rose)

This artwork is inspired by Gol o Morgh, the classical Persian art tradition where the bird and the flower symbolise the lover and the beloved.

In classical Gol o Morgh, the bird and the flower symbolise the lover and the beloved.

In our interpretation, we take this one step further.

We introduce two birds, not as mirrors of one another, but as two lovers turned toward the same source of meaning. Lovers not only of each other, but of divine beauty itself.

One artwork shows a single cobalt-blue nightingale:

the lover alone.

A moment of longing.

A soul mid-song.

The second brings the story together: two birds drawn toward the rose.

Not triumphant.

Not dramatic.

But quietly resolved.

Together, the artworks reflect two states of love:

longing

and presence

Neither louder than the other.

Both held in devotion.

If you’re drawn to art shaped by heritage, symbolism, and quiet meaning, you can explore more pieces inspired by Islamic and cultural traditions in our Islamic art collection.